The Crowd Out Question

This Week: Does GAI crowd out human creators, better attention priors, augmenting llm’s, simulating subjects, llm hypotheses, machine bias

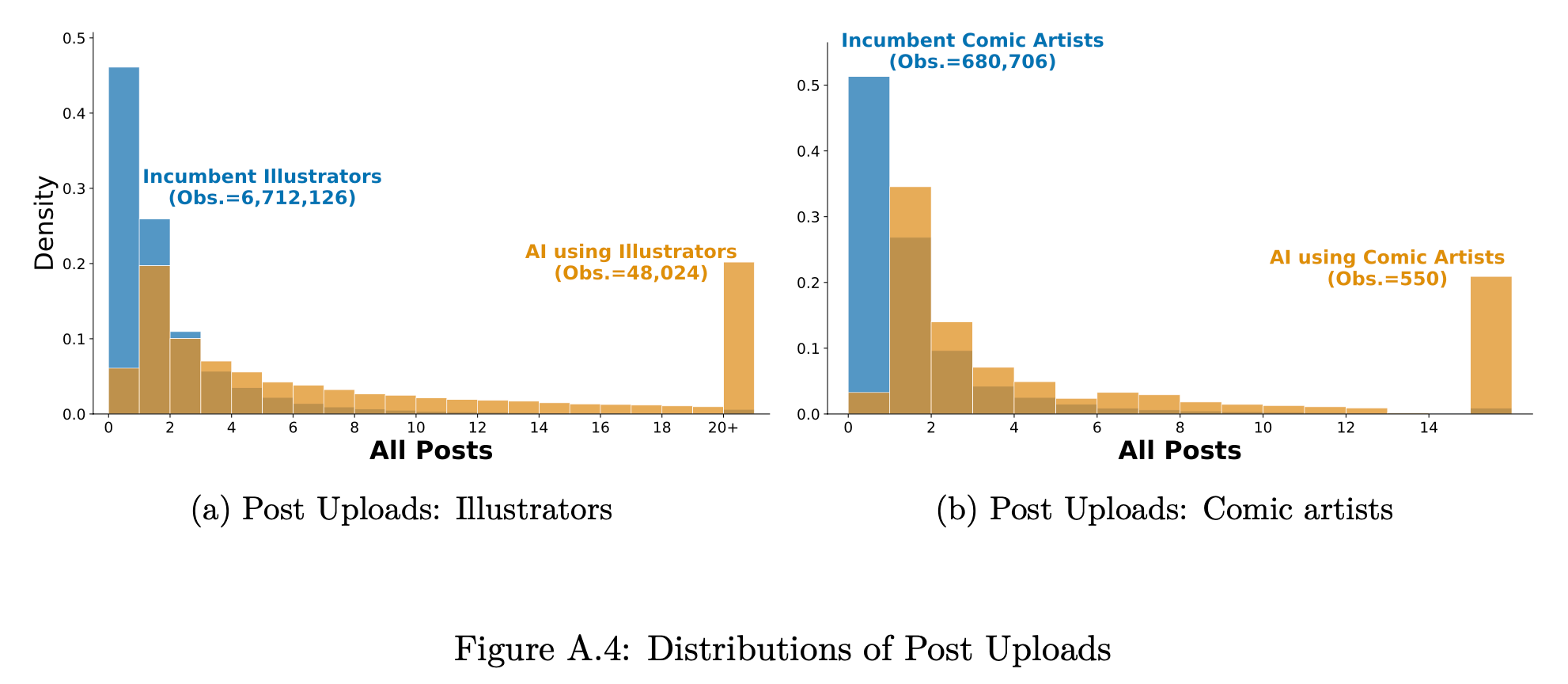

Does Generative AI Crowd Out Human Creators? Evidence from Pixiv

Yes

“First, illustration posts experience a loss of viewer attention, measured by bookmarks, following the AI launch, which can significantly harm creators’ business models. Second, direct competition from AI-generated content plays an important role: illustrators working on intellectual properties (IPs, such as Pokémon) that are more heavily invaded by AI reduce their uploads disproportionately more. We further examine creators’ responses and show that illustrators with greater exposure to AI avoid using tags favored by AI- generated content after the AI launch and broaden the range of IPs they work on, consistent with a risk-hedging response to AI invasion.”

“On average, our results indicate a 10.1% reduction in post uploads for illustrators (the treated group) following the AI launch. Investigating heterogeneous effects further, we find that (1) com- mercial creators who attach links to commercial websites (e.g., for paid subscriptions) experience a larger chilling effect of 14.3%, and (2) the chilling effect is disproportionately large for creators in the top 1% of productivity, measured by monthly post uploads. The second finding helps explain why our estimated chilling effect is smaller than that reported in some existing papers and implies that analyses focusing on the most popular creators may overstate the chilling effect of the AI launch.”

Kim, S., Jin, G. Z., & Lee, E. (2026). Does Generative AI Crowd Out Human Creators? Evidence from Pixiv (No. w34733). National Bureau of Economic Research.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w34733

You Need Better Attention Priors

Not baaaaaaaad

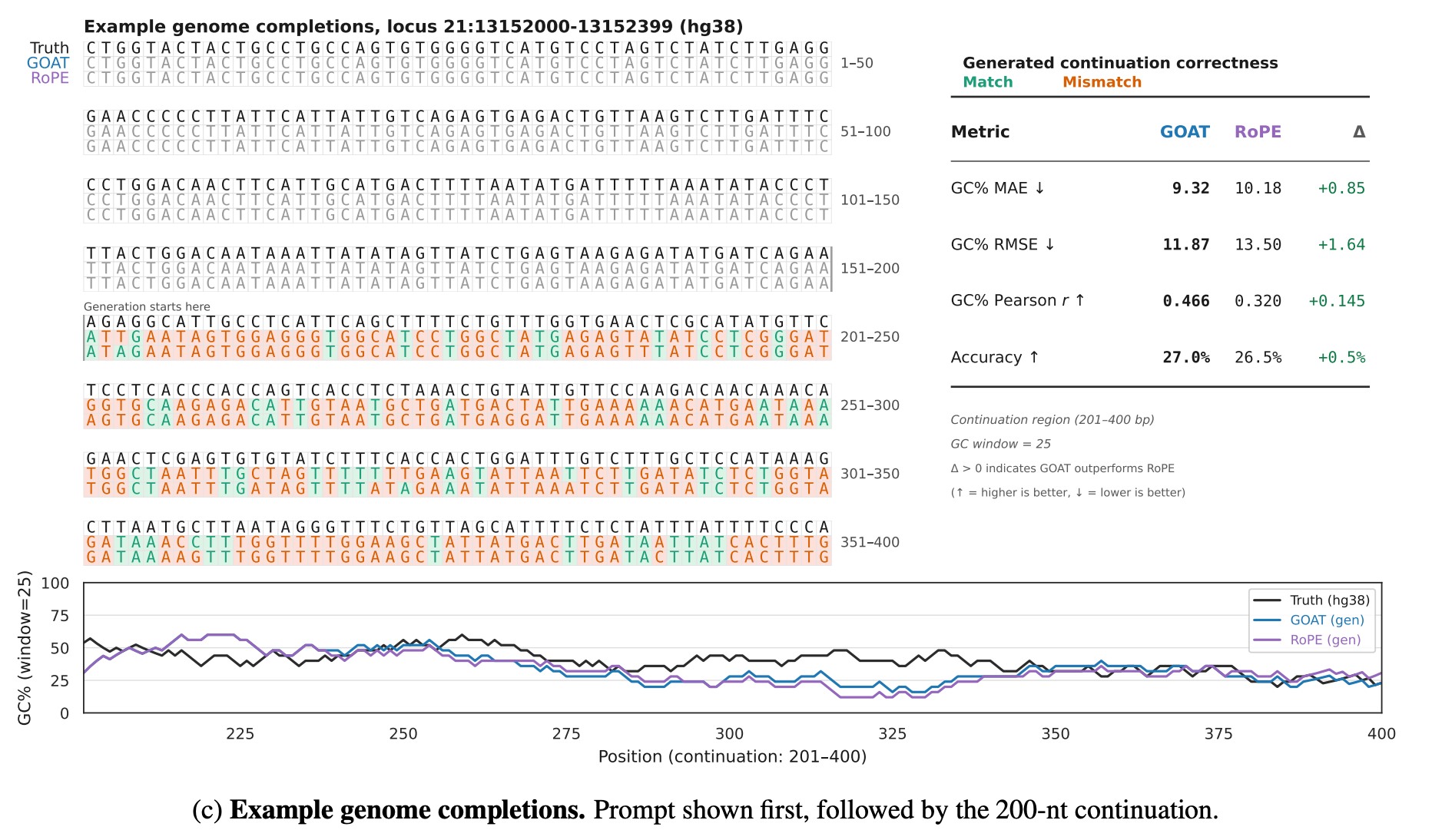

“We introduce Generalized Optimal transport Attention with Trainable priors (GOAT), a new attention mechanism that replaces this naive assumption with a learnable, continuous prior.”

“Attention sinks are tokens that absorb probability mass when the query contains little semantic signal. While often viewed as a learned artifact necessary to satisfy the softmax constraint, our EOT formulation offers a first-principles explanation: sinks are the optimal solution to the KL regularized objective in low-signal regimes.”

“This work identifies that the fragility of standard selfattention, manifesting as poor length generalization and emergent attention sinks, stems from the implicit assumption of a uniform prior within the mechanism’s EOT formulation.”

Litman, E., & Guo, G. (2026). You Need Better Attention Priors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2601.15380.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.15380

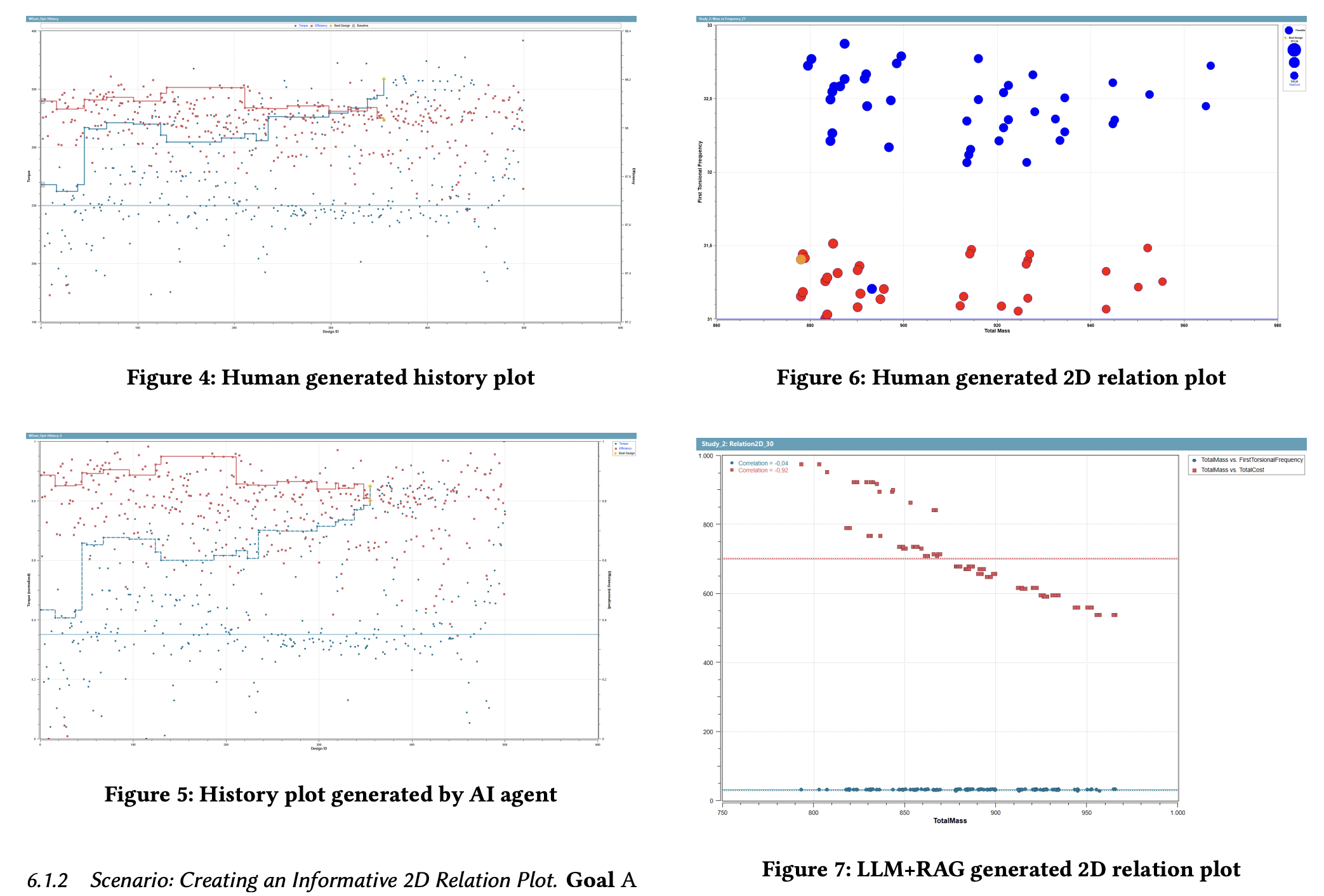

How to Build AI Agents by Augmenting LLMs with Codified Human Expert Domain Knowledge? A Software Engineering Framework

Reading data can be generally quite hard

“We propose a software engineering framework to capture human domain knowledge for engineering AI agents in simulation data visualization by augmenting a Large Language Model (LLM) with a request classifier, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) system for code generation, codified expert rules, and visualization design principles unified in an agent demonstrating autonomous, reactive, proactive, and social behavior. Evaluation across five scenarios spanning multiple engineering domains with 12 evaluators demonstrates 206% improvement in output quality, with our agent achieving expert level ratings in all cases versus baseline’s poor performance, while maintaining superior code quality with lower variance.”

“This challenge is particularly acute in data visualization, where creating effective charts requires both domain knowledge and visualization expertise. Non-experts typically default to familiar chart types because selecting appropriate techniques for complex data remains difficult [11].”

“The system enables non-experts using simple prompts to generate visualizations that correctly apply nuanced expert rules—such as dashed lines for nonconverged variables—that even human engineers sometimes miss.”

Kulyabin, M., Fuhrmann, I., Joosten, J., Pacheco, N. M. M., Petridis, F., Johnson, R., ... & Olsson, H. H. (2026). How to Build AI Agents by Augmenting LLMs with Codified Human Expert Domain Knowledge? A Software Engineering Framework. arXiv preprint arXiv:2601.15153.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.15153

Simulating Subjects: The Promise and Peril of Artificial Intelligence Stand-Ins for Social Agents and Interactions

There can be a lot of wisdom in those unexpected ways

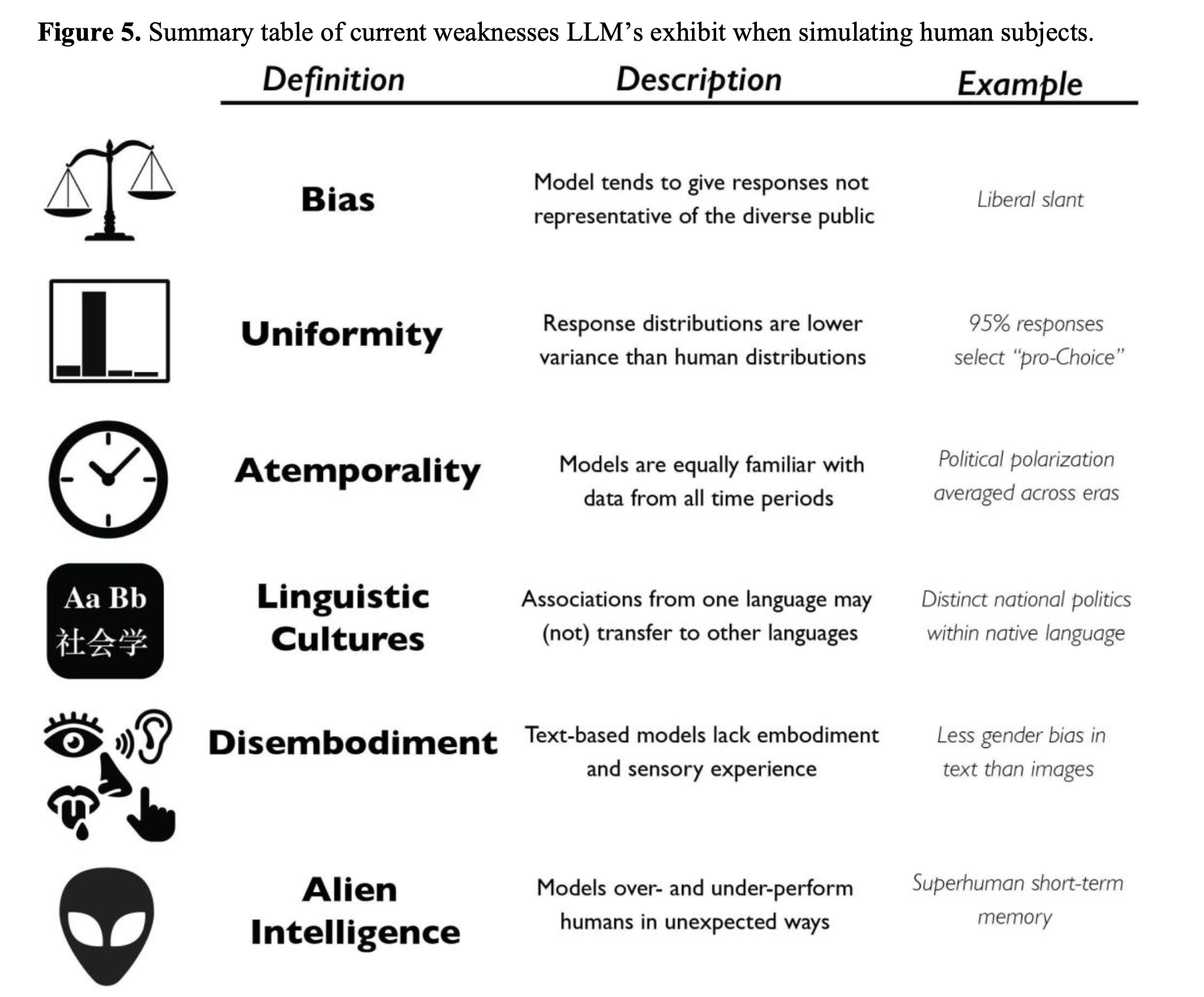

“We then identify six characteristics of current models that are likely to impair realistic simulation human subjects: bias, uniformity, atemporality, impoverished sensory experience, linguistic cultures, and alien intelligence.”

“Despite these similarities, however, an LLM’s mind remains profoundly different from a human mind, and while their command of language makes it easy to anthropomorphize them, a number of observations suggest that LLMs continue to cognize in a way very alien to our own. The “alien intelligence” of LLMs warrants special caution precisely because these models are deceptively similar to humans. Even in extended interactions, it can be nearly impossible to tell if one’s conversation partner is human or AI. Yet at critical moments, the hidden, internal differences between these models and human minds may lead to profoundly inhuman outputs, which could severely distort a simulation study’s findings.”

Kozlowski, A. C., & Evans, J. (2025). Simulating Subjects: The Promise and Peril of Artificial Intelligence Stand-Ins for Social Agents and Interactions. Sociological Methods & Research, 00491241251337316.

https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/vp3j2_v3

Why it Works: Can LLM Hypotheses Improve AI Generated Marketing Content?

But is it upworthy?

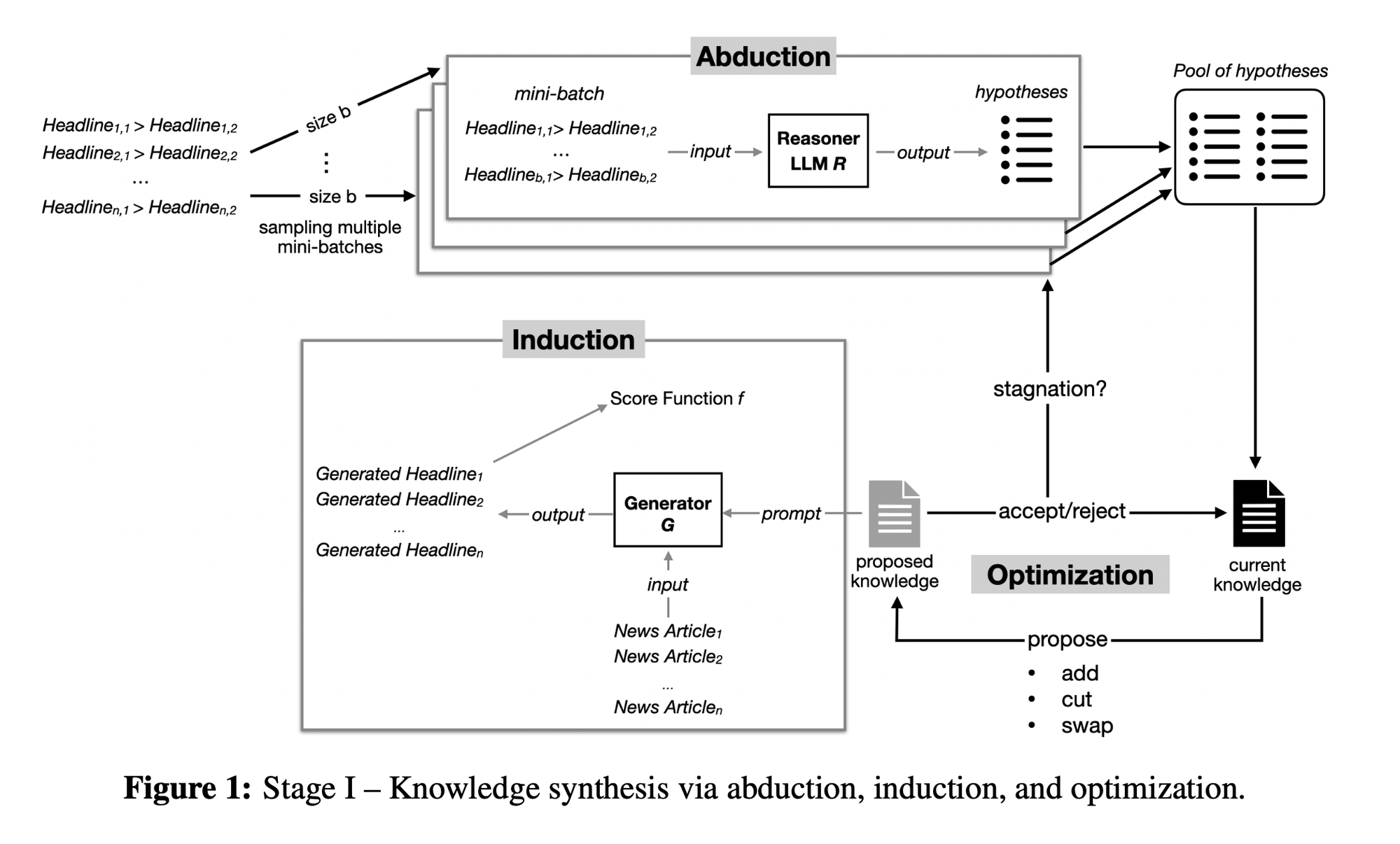

“We propose a principled knowledge-alignment framework that moves beyond merely what works to why it works. In our approach, an LLM iteratively generates hypotheses about mechanisms (e.g., emotional language, narrative framing) to explain observed performance differences on a small set of data (abduction), then validates them on held-out data (induction). The optimized set of validated hypotheses form an interpretable, domain-specific knowledge base that regularizes fine-tuning via Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), constraining the model toward generalizable principles. Our LLM-based approach extends the tradition of theory-guided machine learning to domains where relevant knowledge is tacit and therefore hard to explicitly encode in models.”

“The empirical results on the Upworthy headline dataset confirm the value of our framework. Knowledge-guided fine-tuning improves performance on catchiness and relevance, while also mit- igating reward hacking behaviors such as excessive clickbait. These gains are particularly strong in low-data (limited number of A/B tests) settings, where validated hypotheses provide guidance that compensates for a limited number of A/B tests for training. This property is practically impor- tant: firms often face limited access to training data, since user preference experiments are costly and time-consuming. The ability to inject strong priors via natural-language hypotheses enables managers to accelerate time-to-market while reducing reliance on extensive experimentation. By guiding models toward deeper behavioral drivers, knowledge guidance balances immediate engagement goals with long-term brand trust.”

Wang, T., Sudhir, K., & Zhou, H. (2025). Why it Works: Can LLM Hypotheses Improve AI Generated Marketing Content?. Available at SSRN 5437276.

https://thearf-org-unified-admin.s3.amazonaws.com/MSI/2025/MSI_Report_25-149.pdf

Machine Bias. How Do Generative Language Models Answer Opinion Polls?

The representative hypothesis

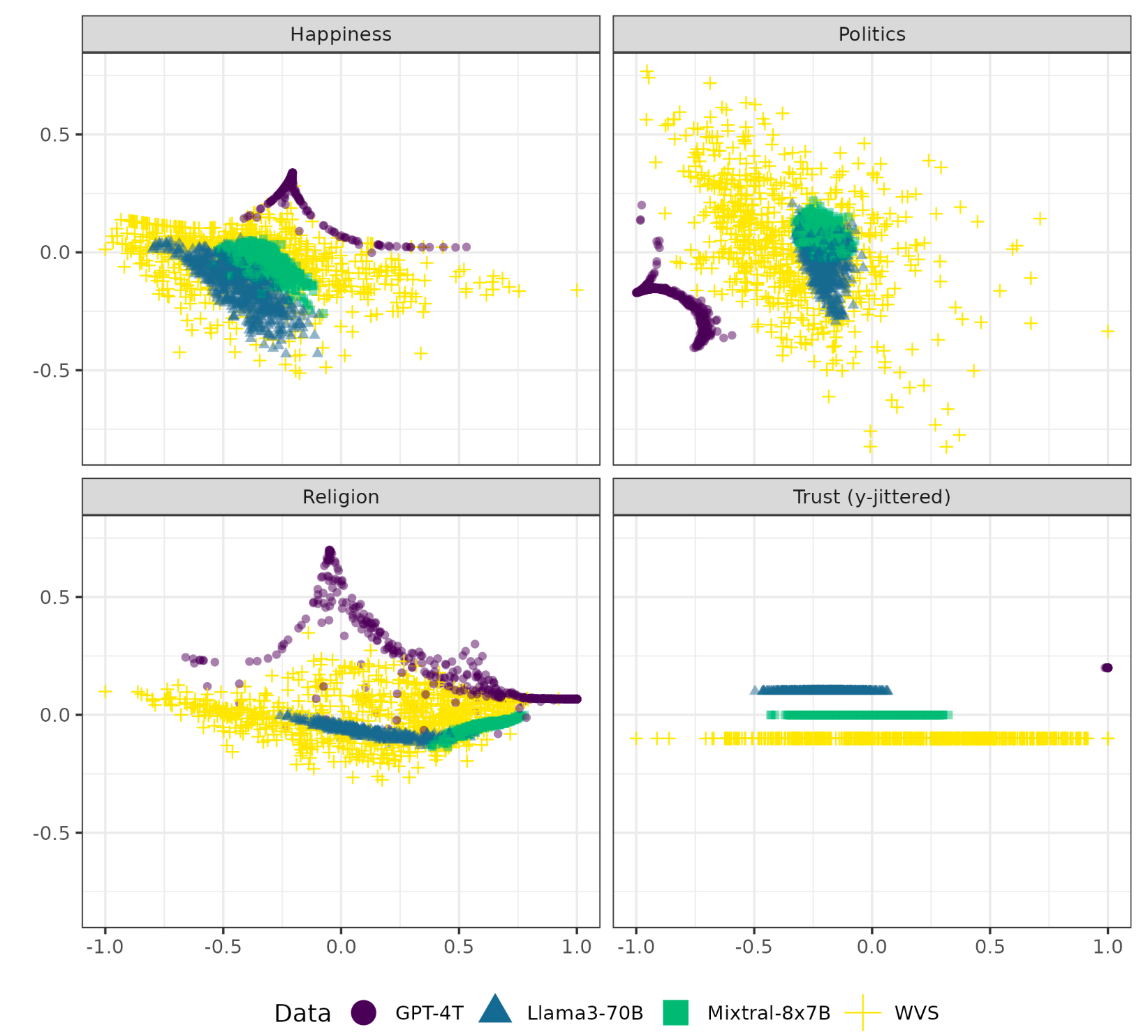

“In this article, we demonstrate that these critics are right to be wary of using generative AI to emulate respondents, but probably not for the right reasons. Our results show i) that to date, models cannot replace research subjects for opinion or attitudinal research; ii) that they display a strong bias and a low variance on each topic; and iii) that this bias randomly varies from one topic to the next. We label this pattern “machine bias,” a concept we define, and whose consequences for LLM-based research we further explore.”

“But high-quality surveys—robust questionnaire design, repeated measures, representative samples—demand advanced skills, take time, and are costly. They are also in crisis. Survey research response rates have been declining for decades (to as low as 1 percent in the polls for the 2024 US presidential election) (Williams and Brick, 2018), which to some extent stems from the decline of landline phones and associated problems of drawing random samples (Dutwin and Buskirk, 2021), and issues of motivating participants to fill in questionnaires online (Daikeler et al., 2019). Massive cohort study endeavors such as the US National Children’s Study and the UK Life Study had to be canceled in the last decade due to lack of volunteer participants (Pearson, 2015). These low response rates hinder their representativity, especially for hard-to-reach parts of the population.”

“We label the idea that LLMs can accurately simulate human populations as the “representative hypothesis.””

“Our experiment shows that current LLMs not only fail at accurately predicting human responses, but that they do so in ways that are unpredictable, as they favor different social groups from one question to another. Moreover, their answers exhibit a substantially lower variance between subpopulations than what is found in real-world human data. We call this theory the “machine bias” hypothesis, according to which LLM errors do not stem from imbalanced training data.”

“One contribution of this study is to advocate for a precise definition of “social bias” in LLMs’ responses. We contend that in order to establish the existence of such a bias, we need to demonstrate that the model consistently favors the position of a specific social group. In other words, we need to clearly distinguish between bias (a simple deviation from the truth) and social bias.”

Boelaert, J., Coavoux, S., Ollion, E., Petev, I., & Präg, P. (2025). Machine Bias. How Do Generative Language Models Answer Opinion Polls?. Sociological Methods & Research, 00491241251330582.

https://hal.science/hal-04849013/document

Reader Feedback

“Farms mechanize, productivity increases, people concentrate in cities. Factories mechanize, productivity increases, people disperse in suburbs. Offices mechanize, productivity increases, people …. ?”

Footnotes

I’m deep into the POCs.

And I have a few observations.

Obligatory declaration:

Synthetic populations are counterfactual simulation tools, not surveys. They formalize assumptions and explore what if scenarios. Results reflect model behavior, not real-world measurement.

Synthetic populations make different sounds than organic ones. You have to listen to enough music to hear the distinction. To the extent they have minds at all, they’re alien. They have alien minds.

And that’s useful because you have a choice when you encounter something unusual. When a synthetic population produces an unusual answer, you can decide to double click on those alien assumptions. Or you can decide to ignore it. You can ask an unusual question and get an unusual answer.

Why are pollsters hired? If the goal is to generate a feeling of certainty, because the poll has a predictive value of what will likely happen in the future, then polling certainly promises that feeling. We made it into a sport in the 2010’s (”He got 50 out of 50 states correct!”). Those who work with polling know about the certainty issue. The most extreme example I can think of: the social event organizing apps Luma and Meetup contain a poll. The user fills out a form signalling that they intend to attend an event. And then the organizer then looks at the faces in the room of those who show up and notices the difference. trollface.gif

Given that access to quality organic attention is on the decline, the desire for synthetic populations to replace organic ones is so strong. Imagine if you didn’t need to consult those pesky humans before deciding! And so there’s a grand bargaining about certainty to be made. Conversations about certainty-as-a-product are rather unpleasant, so I understand why we’re avoiding them.

Sometimes people hire pollsters because they’re engaged in search for advantage, intuition, or differentiation. They may eventually want certainty, but they are not in a state of premature convergence towards it. In today’s newsletter, consider how Wang and Zhou (2025) use A/B headline tests to squeeze hypotheses about link-bait. A form of ground truth is in the actual observed treatment effects, which can be used to inform future tests. That’s how we learn.

That’s what I’m gathering from the POC’s.

More stories to come.

Never miss a single issue

Be the first to know. Subscribe now to get the gatodo newsletter delivered straight to your inbox