The Hotter Mess

This week: The Hot Mess of AI, act or clarify, thoughtbubbles, agentic reasoning, accelerating scientific research, middlegames

The Hot Mess of AI: How Does Misalignment Scale With Model Intelligence and Task Complexity?

Screeches Incoherently

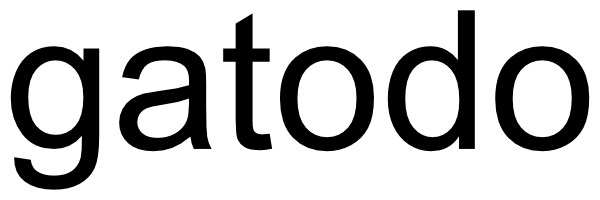

”Will they fail by systematically pursuing goals we do not intend? Or will they fail by being a hot mess, and taking nonsensical actions that do not further any goal? We operationalize this question using a bias-variance decomposition of the errors made by AI models: An AI’s incoherence on a task is measured over test-time randomness as the fraction of its error that stems from variance rather than bias in task outcome. Across all tasks and frontier models we measure, the longer models spend reasoning and taking actions, the more incoherent their failures become.”

“However, in several settings, larger, more capable models are more incoherent than smaller models.”

“Second, variance typically accumulates over a trajectory unless there is an active correction mechanism (like ensembling, Fig. 7). When an AI acts in the real world, actions are often irreversible. Therefore, it will often be impossible or impractical to correct for noise introduced by model actions.”

Hägele, A., Gema, A. P., Sleight, H., Perez, E., & Sohl-Dickstein, J. (2026). The Hot Mess of AI: How Does Misalignment Scale With Model Intelligence and Task Complexity?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2601.23045.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.23045

Act or Clarify? Modeling Sensitivity to Uncertainty and Cost in Communication

Mohito

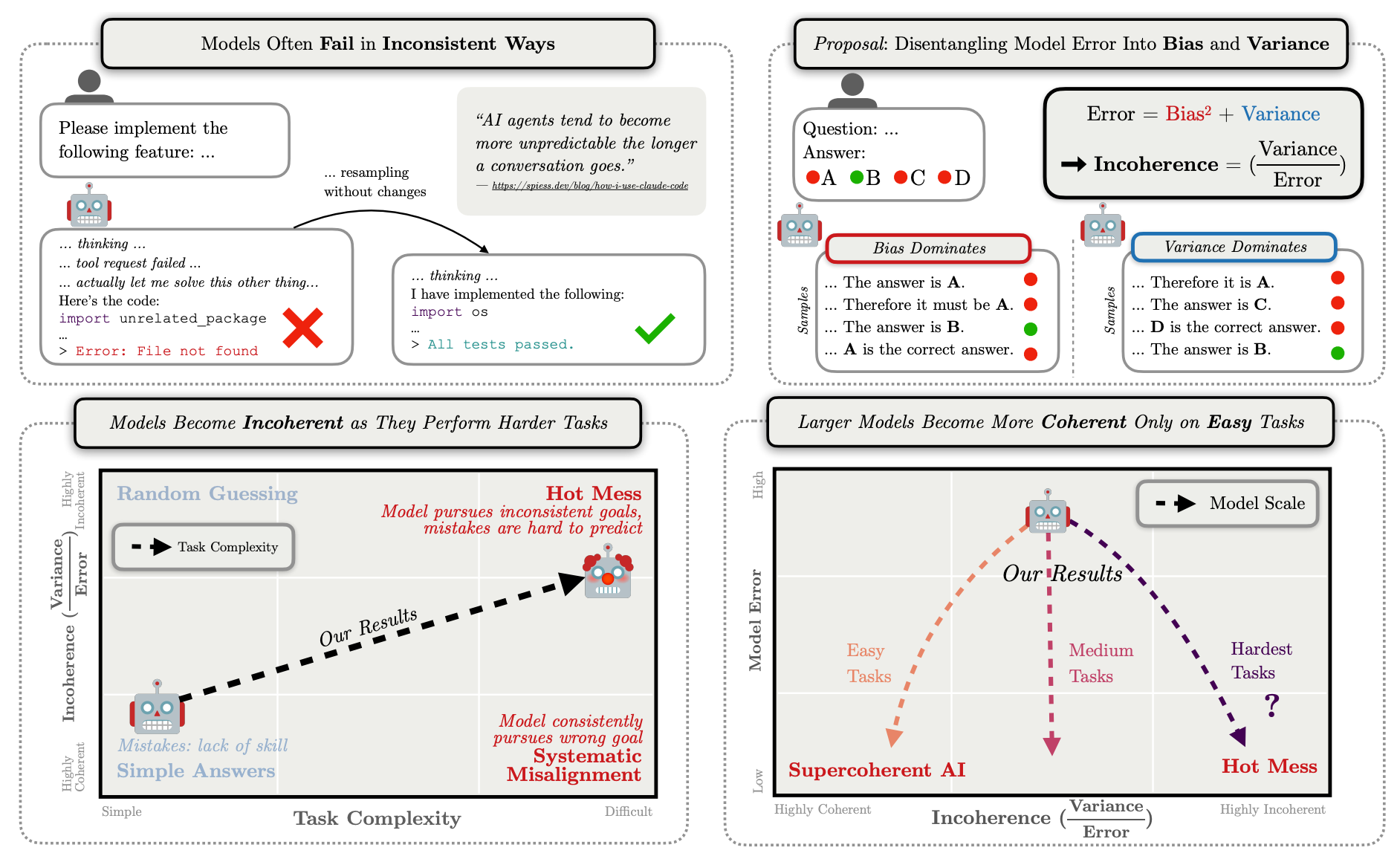

“When deciding how to act under uncertainty, agents may choose to act to reduce uncertainty or they may act despite that uncertainty. In communicative settings, an important way of reducing uncertainty is by asking clarification questions (CQs). We predict that the decision to ask a CQ depends on both contextual uncertainty and the cost of alternative actions, and that these factors interact: uncertainty should matter most when acting incorrectly is costly. We formalize this interaction in a computational model based on expected regret: how much an agent stands to lose by acting now rather than with full information.”

“We propose that this interaction arises because both factors are naturally unified through expected regret (equivalently: the expected value of perfect information; Raiffa & Schlaifer, 1961): agents ask CQs when their best available action risks substantial loss relative to what full information would afford. We test these predictions in a question-answering context where responses are purely linguistic (Experiment 1), then ask whether the same tradeoff governs choices between clarification and non-linguistic action (Experiment 2), before formalizing the account in a layered computational model based on expected regret.”

“These results provide empirical support to our hypothesis that communicators are sensitive to uncertainty (asking for clarification when uncertainty is high), and that this propensity is modulated by costs of alternataive [sic] responses.”

“Several further avenues remain for future work. We have focused on the costs of not asking (namely risking error from acting under certainty). But there are also costs to asking: CQs take time and effort, delay action, and may carry social costs such as appearing incompetent to a superior. While the parameter 𝑐 in our model could be interpreted as the cost of asking, we did not explicitly manipulate this; future experiments might do so through time pressure or social context.”

Tsvilodub, P., Mulligan, K., Snider, T., Hawkins, R. D., & Franke, M. (2026). Act or Clarify? Modeling Sensitivity to Uncertainty and Cost in Communication. arXiv preprint arXiv:2602.02843.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2602.02843

Thoughtbubbles: an Unsupervised Method for Parallel Thinking in Latent Space

Finally, a bubble that won’t pop

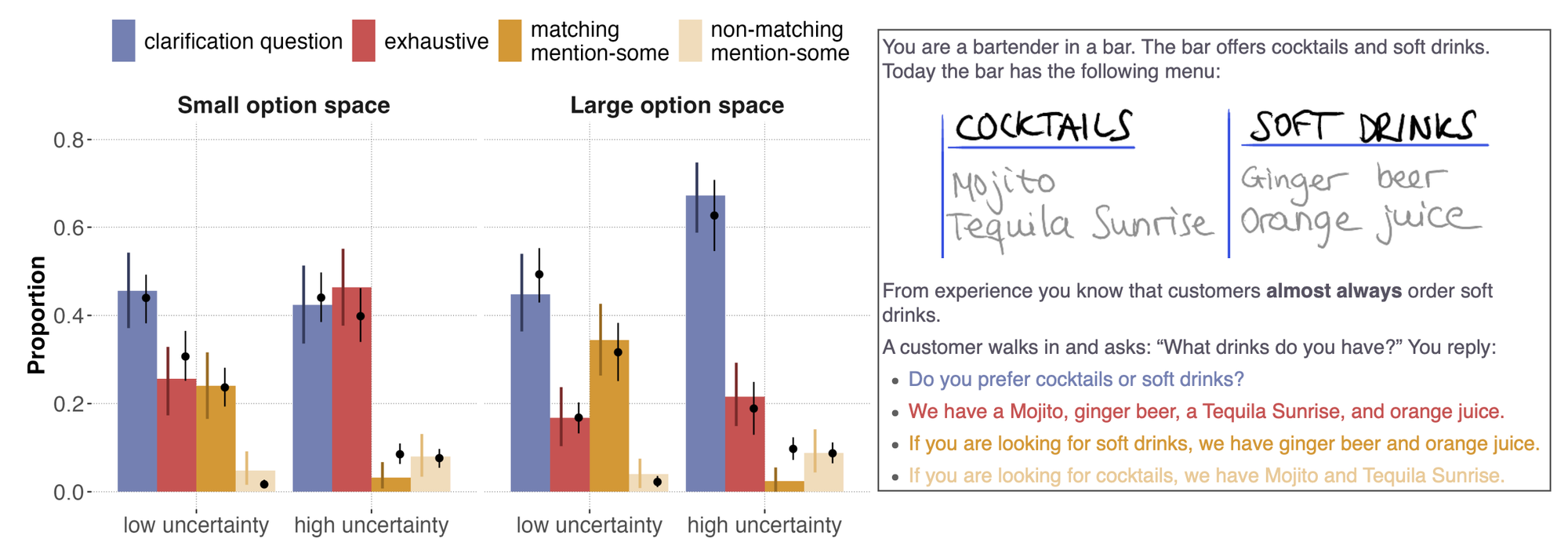

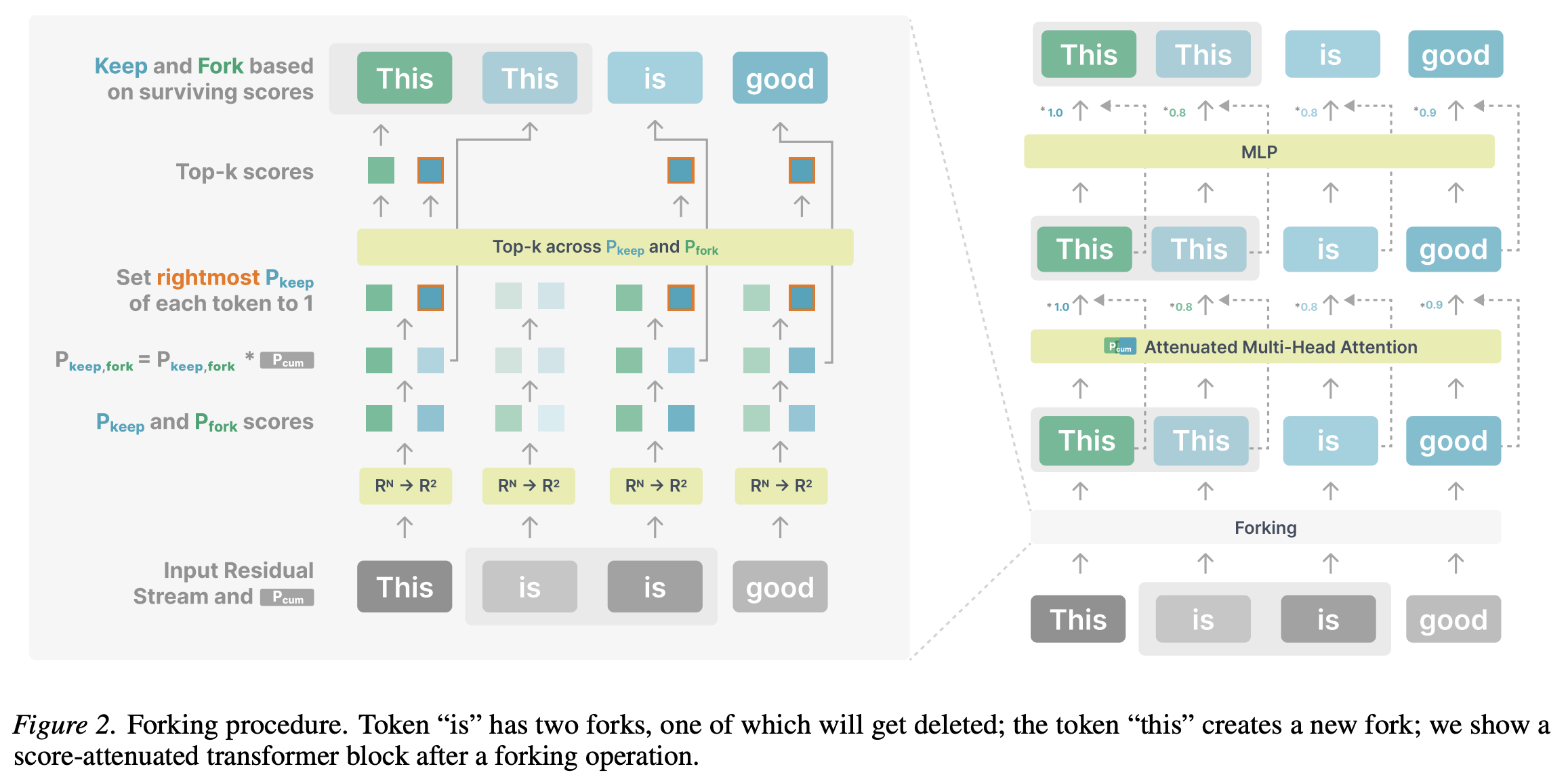

“Current approaches for scaling inference-time compute in transformers train them to emit explicit chain-of-thought tokens before producing an answer. While these methods are powerful, they are limited because they cannot be applied during pretraining and rely solely on serially-generated, natural-language verbalization. In this work, we propose Thoughtbubbles, a transformer variant that natively performs parallel adaptive computation in latent space by learning to fork or delete residual streams. Thus, tokens requiring more computation can form a “bubble” of cloned residuals in the middle of the network.”

“To achieve parallel computation, we want to allocate more residual streams corresponding to tokens that require more computation. To enable this, we propose a special type of operation named “forking”, described in Section 2.3, which can duplicate or remove some residual streams for future computation. The amount of forking is controlled by assigning a “cumulative score” between 0 and 1 to each residual stream. This score can be interpreted as the stream’s existence indicator. In the forking operator, for each residual, the score is multiplied by two newly computed scores: “keep score” for updating the current stream, and a “fork score” indicating the importance of creating a new copy of this stream.”

“We demonstrate the efficacy of our method via a suite of zero-shot evaluations as well as gsm8k evaluations in both computation and parameter matched settings at 1.9B parameters; furthermore, in our scaling experiments between 150M-772M parameters, we discovered that our method at a smaller 319M scale outperformed baselines at 772M scale.”

Liu, H., Murty, S., Manning, C. D., & Csordás, R. (2025). Thoughtbubbles: an Unsupervised Method for Parallel Thinking in Latent Space. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.00219.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.00219

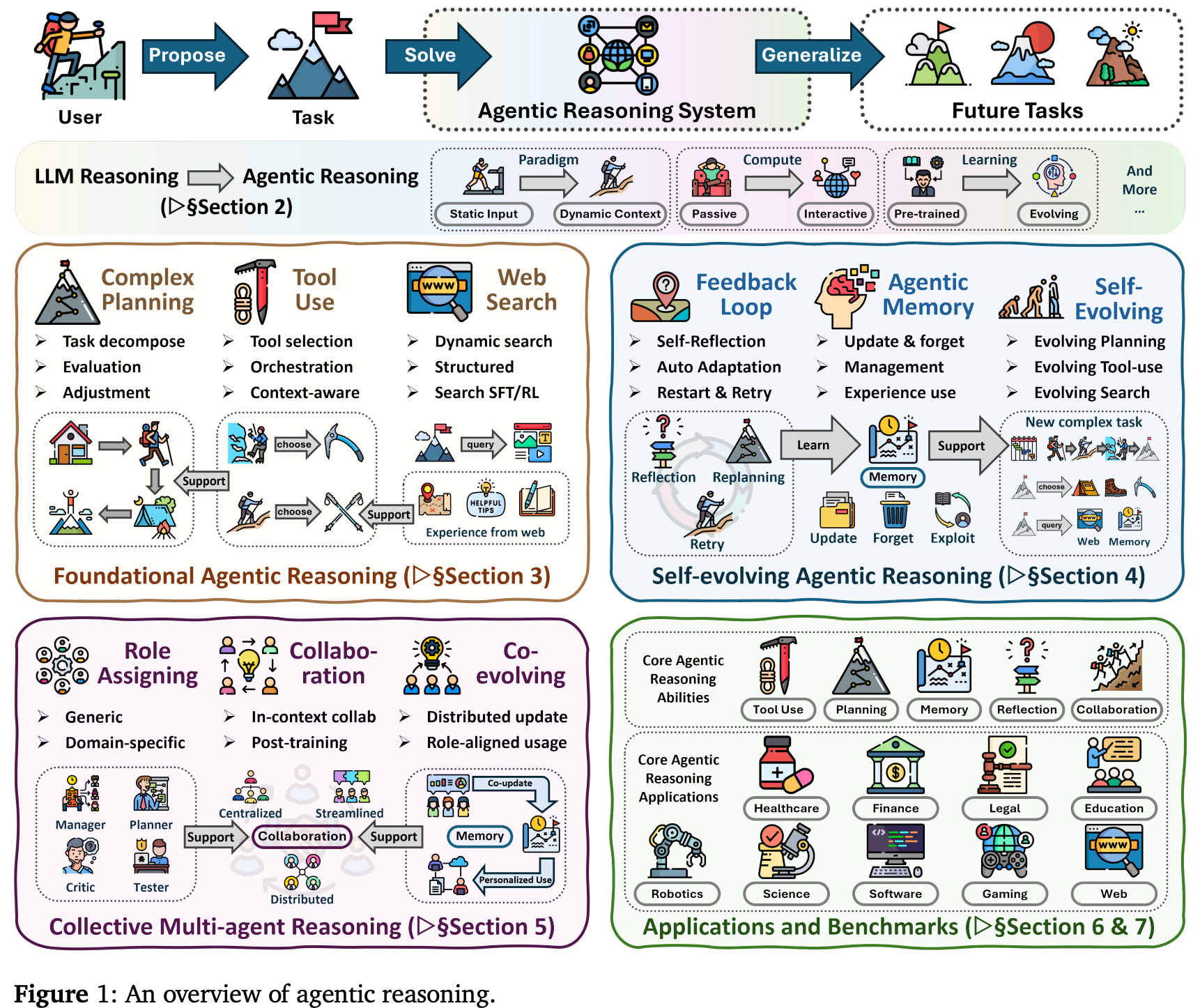

Agentic reasoning for large language models

At 125 pages and 797 citations…it’s a girthy read

“The emergence of agentic reasoning marks a paradigm shift, bridging thought and action by reframing LLMs as autonomous agents that plan, act, and learn through continual interaction. In this survey, we provide a systematic roadmap by organizing agentic reasoning along three complementary dimensions. First, we characterize environmental dynamics through three layers: foundational agentic reasoning establishes core single-agent capabilities, including planning, tool use, and search, that operate in stable environments; self-evolving agentic reasoning examines how agents refine these capabilities through feedback, memory, and adaptation in evolving settings; and collective multi-agent reasoning extends intelligence to collaborative scenarios where multiple agents coordinate roles, share knowledge, and pursue shared goals.”

“Recent advancements have shifted multi-agent systems from fixed, hand-designed coordination toward training paradigms that enable agents to evolve over time [26, 446, 414]. Training multi-agent systems to evolve represents a critical step toward realizing adaptive, long-horizon intelligence beyond static coordination. In this emerging paradigm, agents improve collectively through interaction, feedback, and shared memory, rather than isolated or independently optimized behaviors. By embedding reasoning into the learning loop, via reinforcement learning [447], self-play [448], curriculum evolution [413], and verifier-driven feedback [449], multi-agent systems can internalize coordination strategies, address inter-agent credit assignment, and progressively refine divisions of labor. This evolution transforms multi-agent reasoning from a static ensemble of cooperating LLMs into a self-improving organization that adapts its structure, communication patterns, and policies in response to task complexity and environmental change [450].”

Wei, T., Li, T. W., Liu, Z., Ning, X., Yang, Z., Zou, J., ... & He, J. (2026). Agentic reasoning for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2601.12538.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.12538

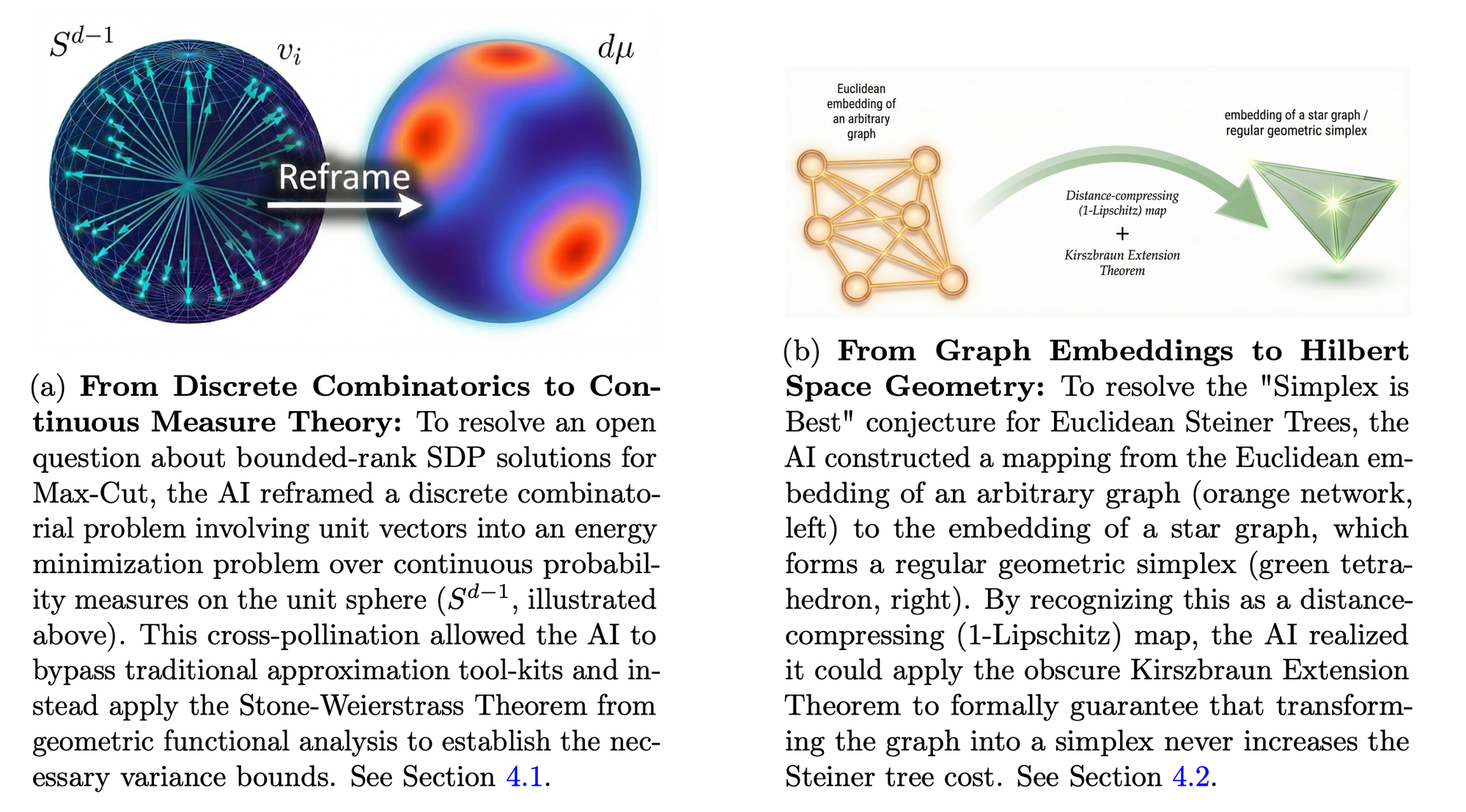

Accelerating Scientific Research with Gemini: Case Studies and Common Techniques

More girth

“This paper documents a series of independent experiments where researchers utilized advanced AI models to tackle specific, often long-standing, open problems in their respective fields. The results range from resolving conjectures in information theory and submodular maximization to deriving exact analytical spectra for cosmic strings and improving bounds for graph algorithms.”

“Algorithmic Insight and Optimization: In algorithmic research, AI can propose novel data structures or analysis techniques (e.g., adapting quadtrees for different norms) to improve time complexity bounds.”

“Just as the advent of calculators and computational algebra systems revolutionized applied mathematics in previous decades, the ability to rapidly iterate on abstract reasoning with a tireless, knowledgeable AI collaborator promises to dramatically reduce the friction of theoretical execution. By embracing this collaborative paradigm, understanding its failure modes, and building the automated verification pipelines of the future, researchers can tackle more ambitious problems, explore broader hypothesis spaces, and ultimately accelerate the pace of scientific discovery.”

Woodruff, D. P., Cohen-Addad, V., Jain, L., Mao, J., Zuo, S., Bateni, M., ... & Mirrokni, V. (2026). Accelerating Scientific Research with Gemini: Case Studies and Common Techniques. arXiv preprint arXiv:2602.03837.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2602.03837

End Game Play

Middlegames matter

“Endgame play is a symptom of simulation. Engines exhausted the opening and middlegame of chess so humans skip to the only phase that isn’t pre-computed. Both sides of a modern war can model the front, model the force projection, model the outcome— so the opening collapses and what gets fought is the narrow sliver simulation can’t price. Musk simulates forward from the terminal state and treats everything between here and there as bottleneck. Already computed. Already recited.”

https://minutes.substack.com/p/end-game-play

Reader Feedback

“It is alien because it is not cybernetic”

Footnotes

Assume that a segment is a unit of need with willingness to pay.

Segmentation is the act of finding and/or defining segments.

There are many kinds of segments: customer, market, addressable, and controversially the persona.

A customer segment can be discovered in the transactional log.

A market segment are buyers who refer to one another when making a purchasing decision (that’s a Geoffrey A. Moore reference), and clues can be found in the transactional log, and outside of it.

An addressable segment can have a treatment applied to it: a piece of addressable direct mail, a banner ad, a video ad, a search engine results page, a newsletter (hello!), or a linear ad.

And a persona is an instrument to induce empathy for consumers in the marketing and/or product organization.

The extent that these distinctions matter depends on the need of the asker.

The bit I’ve been struggling with this week in particular is the act, job, verb, of segmentation.

It’s a difficult task. In fact, even with a lot of processing and signal extraction, it remains too hard. The research handbook in common use for the management sciences is a 471 page monster. Then there are base skills, akin to reading cursive or sheet music, that go along with it. I watched myself writing a patient and generous alpha tester how to read a crosstab table. And then laughed at myself for writing it.

Segmentation should be easier.

Never miss a single issue

Be the first to know. Subscribe now to get the gatodo newsletter delivered straight to your inbox